The postdoc holding tank (TRR-VI)

August 30, 2012 3 Comments

Uncovering the biggest bulge under that rug

I have poked fun (1) at the Tilghman-Rockey report (TRR; 2) for failing to notice key issues or evading them by shoving them under rugs. In fairness, the TRR—like all the rest of us—must have felt overwhelmed by the confusing complexity of multiple intersecting problems. Until about 2003, America’s long love affair with biomedical research fueled exciting discoveries, growth in numbers (and often in quality) of investigators, graduate programs, and postdocs, and relentless expansion of research universities, along with a host of festering troubles that were masked for decades by 9% average annual NIH budget increases (3, 4). Early in the 21st century, a second problem appeared when that love affair was interrupted by a decade of flat-line NIH budgets, economic recession, and Congressional gridlock—an interruption that began to uncover troubles that had long festered beneath the surface (3). One of these troubles, the brimming postdoc holding tank, began in the 1990s and is still with us. Trying to combat it, we bump our shins against hard questions:

- How many biomedical bench scientists, including trainees and the PIs they hope to become, can the US support? Will that change? In what direction?

- Can we maximize scientific contributions of foreign biomedical PhDs without depressing the market for PhDs who are US citizens?

- Can we accelerate transfer of postdocs into the permanent workforce?

- Would more staff scientists help? If so, how can we make that happen?

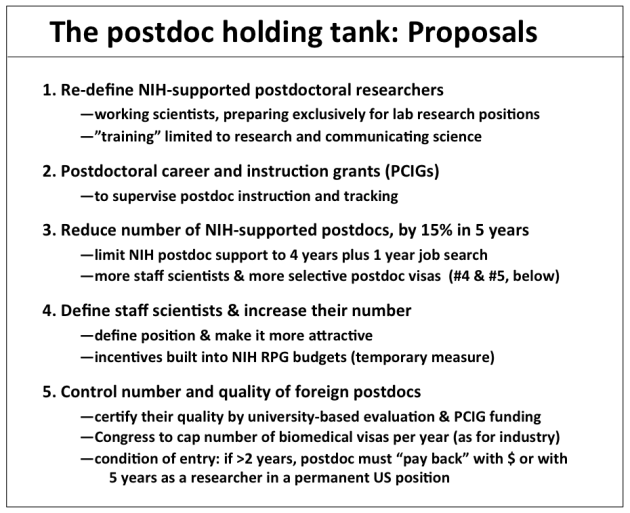

Because none of these inescapable questions has a clear, quantitative answer, in handling them we should follow several principles: (i) provisional answers change with time, so we must remain flexible and receptive to change; (ii) in straitened financial times, selective austerity is prudent and necessary; (iii) actions based on provisional judgments should be accompanied by vigorous attempts to obtain quantitative data to support, refute, or modify the initial approach; (iv) change must be deliberate and always subject to modification based on credible data, but never come as a sudden surprise for postdocs, PIs, or institutions; (v) collaborative action is essential, so all stakeholders—PIs, trainees, NIH, universities, even Congress—need to hone their skills in the arts of persuasion, compromise, and adroit application of carrots and sticks; (vi) recognizing that any useful action affects the whole enterprise, our actions must create a flexible new business model for US biomedical research. The new model will curtail and re-direct research expansionism and soft-money salaries for research faculty, revise peer review and NIH policy to adjust distribution of resources, and—with better data—manage the number, quality, and career directions of both US-trained and foreign PhDs (4, 5). All these topics will reappear in BiomedWatch. With that prelude, I present five proposals for shrinking the postdoc holding tank and changing the postdoc’s role. (Proposal numbers do not correspond to any specific TRR recommendations; see Table and 6.)

Proposal 1. Re-define NIH-supported postdoctoral researchers. To correct confusion about mutual obligations of postdocs and institutions, all newly hired postdocs supported by NIH research project grants (RPGs) or training grants (TGs) will be called “postdoctoral researchers,” not “trainees.” Their obligations are to begin long-term research careers by serving as working scientists. In turn, the institution is obliged to treat them as full-fledged employees, with specified exceptions (proposal 3, below). The supervising PI will outline her/his view of the PI’s “training” obligations before each postdoctoral researcher is hired, and the institution will offer postdocs optional instruction in scientific writing and communication.

This proposal focuses on postdoctoral researchers committed to research careers, but does not envision markedly different experiences for individuals who anticipate research careers in academia vs. industry. In my opinion, the essential skills and expertise developed in postdoctoral research—ability to choose and define an important problem, find an answer or solution, and communicate these to others—constitute excellent preparation for either career direction. Newly minted biomedical PhDs who seek careers not directly engaged in research (e.g., in research-related fields such as regulation, law, business, etc.) should seek further training in those areas, rather than in the laboratory.

By making the parties’ obligations explicit, this proposal confirms today’s unwritten rules in US labs: PIs consider active “training” an option, not a duty, while postdocs manage to learn in the lab, however they can. As grownups, prospective postdocs will continue to choose between PIs who actively help postdocs to learn or those who teach by example rather than by precept (7). But the proposal does require institutions to offer postdocs instruction in writing and communication. Communication skills are conspicuously lacking in many US citizens or foreigners who otherwise qualify as superb beginning scientists, but the much-needed instruction can be skimpy and scattered in US labs, because institutions are loath to spend money training personnel they consider primarily as workers. To make this requirement work, the NIH should devote funds to partial salary support for instructors, via competitive grants (PCIGs; see proposal 2, and 8).

In re-defining the role of a postdoc and setting a maximum number of years (five) for postdoc funding (see proposal 3, below), the NIH should stop funding salaries of “subterfuge postdocs”—that is, postdoctoral researchers who are called something else, as a way to get work out of them without appointing them to faculty positions that allow them to submit grants. There should be only one category of research employee between postdoctoral researcher and faculty status: the staff scientist (proposal 4, below).

Proposal 2. Track progress and careers of all postdocs. The TRR was disappointed to discover how little we know about postdoc numbers and trajectories, both during and after postdoctoral service. To control its future, the US biomedical research enterprise must know the number of its postdocs, their qualifications, their citizenship status, what permanent positions they subsequently take, and how well they fare in those jobs. The main hitches: (i) the federal government cannot legally compel universities to track the many postdocs supported by non-federal sources; (ii) accurate tracking costs time and money. To counter these difficulties, the NIH should require institutions that employ more than a small number of NIH-supported postdocs to apply for and obtain at least one Postdoctoral Career and Instruction Grant (PCIG). PCIGs will pay administrative salaries to help universities supervise instruction of postdocs (proposal 1, above) and monitor their progress (see other proposals, and 8). PCIG applications will be favored from institutions that heed NIH’s request to instruct and monitor all postdocs, including those supported by non-federal grants.

Proposal 3. Reduce number of postdocs supported by the NIH. Although the TRR pointed to difficulties with the postdoc holding tank, it did not argue strongly enough for draining the tank of its oldest denizens or for starting the drainage process now, on a temporary basis, while we await more definitive data. So I propose that NIH impose a four-year cap on postdoctoral funding from any RPG or TG/F, with an optional fifth year under special circumstances (9). This proposal is the first of three needed to reduce the total number of NIH-funded postdocs by 15 % over the next five years.

The urgency of these proposals reflects the following: (i) taken together, flat-line NIH budgets, straitened university budgets, paucity of open tenure-track positions, and loss of biomedical research jobs in industry show the US already has more postdocs than are needed for available jobs; (ii) weak economic growth and political gridlock predict little near-term improvement in this situation, so postdocs’ job prospects will worsen for 5-10 more years; (iii) lagging growth of permanent research positions in academia and industry indicates that the number of excellent job candidates will remain high even if the number of fifth-year postdocs is substantially reduced; (iv) as data accrues, the proposed measures can be strengthened, weakened, or eliminated.

The usual counterargument promotes maintaining a high number of postdocs in US labs by invoking a self-serving premise that amounts, in caricature, to: “Without more than a dozen postdocs to test my brilliant ideas, my lab’s productivity will plummet.” I worry instead about a stronger counterargument: reducing the number of postdocs will not be easy. Nonetheless, we can make it work by accelerating efflux of postdocs (proposals 3 and 4) and reducing their influx (proposal 5). If each of these three proposals reduces the number of NIH-supported postdocs by 5% over the next five years, the 15% goal will be achieved.

Proposal 4. Define staff scientists and increase their number. The TRR weakly endorsed staff scientists (10), but said nothing about what they do or how to increase their numbers in academic labs. Fortunately, the right people do exist. PIs of successful labs find at least one postdoc every few years with the right qualifications: keen intelligence, excellent experimental skills, burning desire to solve problems, and a preference for tackling research problems rather than for the hassles of an academic PI. Such individuals need the right opportunity, with a living wage and a measure of security. So, NIH should define what a “staff scientist” does, require a suitable job classification in universities, and construct incentives for RPG funding of staff scientist positions. Thus:

- Definition: a staff scientist has an MS or PhD degree, performs and analyzes results of several kinds of experiment with unusual skill, is expert in at least one area of special interest to the lab (e.g., microscopy, deep sequencing, etc.), and can teach and help supervise postdocs and graduate students.

- Job classification (by the institution): salary higher than a senior postdoc, lower than a faculty PI; supported by funds from outside the university; not a faculty member or permitted to apply for grants; benefits comparable to those of other institution employees; job security for the duration of the PI’s grant, with an extra “bridging year” funded by the institution or by other mechanisms (see 11).

- Incentives for the PI to hire a staff scientist. For a trial period of three years—longer if the staff scientist initiative is successful—the NIH will allow PIs of newly awarded or competitively renewed RPGs to substitute a staff scientist position for that of one postdoc per grant, subject to important stipulations (11).

- Incentives for the prospective staff scientist. In addition to higher salary and benefits, NIH will require PIs and institutions to implement long-term plans, activated if an RPG supporting a staff scientist is not renewed, for “bridging” one year of her/his salary and benefits (12).

These measures should make the idea attractive to PIs, staff scientists, and reviewers. After five years of close monitoring, the NIH can modify the initiative.

5. Control the number and quality of foreign postdocs. Influx of foreign biomedical postdocs into US labs is unlimited, owing to lack of coordinated action by Congress, the US immigration service, research institutions, PIs, and federal agencies like NIH. This uncontrolled influx brings cheap, smart workers to US labs, along with serious problems: a depressed job market for US-trained biomedical PhDs and the ever-expanding postdoc holding tank (13). I add a personal observation: non-citizen postdocs are not all first-rate researchers. My guess is that at least 20% of these individuals (and about the same proportion of US citizen postdocs) lack either the education or the ability necessary to contribute usefully to US biomedical research. This is not quantitative evidence, but while seeking such evidence ordinary prudence suggests that we subject prospective postdocs (foreign and domestic) to more stringent selection.

The TRR made no serious attempt to correct knotty postdoc problems, perhaps because it felt the NIH by itself can’t do much about them. In my view, the NIH must take the lead to bring major stakeholders together and coordinate efforts to accomplish three essential tasks. The first task is to mobilize research institutions, helped by partial funding from the PCIGs described above, to coordinate an effort to monitor and improve the quality of all postdocs, foreign and US citizens. Quality will be monitored before acceptance into a lab, upon completion of postdoctoral service, and in their later careers (14). Redacted to prevent identification of actual individuals, this information will be made publicly available for analysis by NIH, the Immigration service, and others.

Second task: Congress must cap the annual number of visas issued to foreign postdocs who seek positions in academic and other not-for-profit laboratories. Such a cap will resemble those already imposed on visas for highly skilled non-citizen degree-holders seeking jobs in business and industry. Perhaps Congress wants to protect Americans looking for jobs in industry, but has been persuaded that an unlimited supply of cheap foreign workers is necessary to sustain scientific innovation. Research institutions and academic PIs sent the latter message to Congress in boom economic times, and it will be hard to convert them to a new view—harder, perhaps, than converting Congress. To convince institutions, PIs, and Congress to cap foreign postdoc visas, we begin with a straightforward argument: as in business and industry, an excess of foreign workers, driven by low pay and inadequate opportunities at home, depresses the market for researchers who are US citizens, who are then shunted into fields less critical for our country’s future. The second, more subtle argument is that the US does not have enough permanent jobs to employ less skilled scientists, but it is still very much in our interest to attract the very best foreign postdocs to US jobs, and so to use relative quality of prospective foreign postdocs as a criterion for issuing postdoc visas. American universities and NIH PCIGs can help judge their quality more accurately, and a cap on their number will motivate them to do so.

Third task: Foreign PhDs or MDs who serve as US postdocs for three years or more should “pay back” the US investment by committing to work for one or more research years in a permanent US position.US citizens supported as postdocs on NIH training grants or fellowships (TG/Fs) already must pay back afterward, by engaging for one year in health-related research and/or teaching. This requirement makes it easier to track their subsequent career choices, but not the choices of foreign postdocs, who can be supported from RPGs but are at present ineligible for TG/F support and thus exempt from the payback obligation. Congress should impose that obligation on foreign postdocs, regardless of the source of their NIH support and (if legally possible) when they are supported by US-based but non-federal sources (e.g., American foundations, institutions, or companies). Requiring their payback for the opportunity to work in cutting-edge US science will help guide the best young foreign scientists into scientific careers in the US. Such guidance will be even more effective if—at the behest of Congress—US immigration authorities couple the payback to accelerating the start of permanent resident status (i.e., a green card).

Six BiomedWatch essays have criticized the TRR’s recommendations, revised many, and come up with new proposals. To summarize the remedies I propose and their rationale, the series will include one additional essay. I hope you will read all seven!

NOTES

1. See previous posts on the TRR, including: The biomedical workforce report (TRR-I); A flood of soft-money PI salaries (TRR-II); Is PhD training too narrow? (TRR-III); NIH support for PhD training (TRR-IV); Postdoc problems (TRR-V).

2. Biomedical Research Workforce Working Group Report. Pdf here.

3. D Korn, et al., The NIH Budget in the “Postdoubling” Era, Science 296, 1401 (2002). See also Why ignore those icebergs (I).

4. MO Lively, HR Bourne, Iceberg Alert for NIH, Science 337:390 (2012). For pdf, go to first paragraph under “Must-read” on the BiomedWatch homepage.

5. See also Why ignore those icebergs? (I), which is cited in note 3, above, and Why ignore those icebergs? (II).

6. Readers may remember that I numbered TRR recommendations 1-9 arbitrarily, in their order of appearance in BiomedWatch. The TRR itself did not number its recommendations, and the numbers I used are entirely independent from “proposal” numbers in the present post.

7. PIs and postdocs can name individual PIs who fit each description exactly, and others for whom the training obligation falls somewhere in between. For instance, HR Bourne, Paths to Innovation (2011) shows the wide distribution on this spectrum of four superb scientists: Michael Bishop, Herb Boyer, Stanley Prusiner, and Harold Varmus.

8. PCIGs will supply partial salary support for personnel in the university’s Office for Postdoctoral Research, which will assume reponsibility for: (i) arranging instruction in scientific writing and communication for postdocs who choose to take advantage of it; (ii) ensuring that NIH rules for postdoc funding are accurately applied; (iii) monitoring postdocs’ qualifications, accomplishments, and whereabouts before, during, and after their postdoctoral service.

9. For instance, a fifth year of NIH would be supported if the postdoc’s progress has been delayed by pregnancy or an illness, with documentation that it is necessary for her/him to obtain a permanent job in another lab. Note that RPG funding for foreign postdocs must not be used to allow them to apply for non-federal postdoctoral funding. The NIH cannot prevent eventual transfer of a foreign postdoc to support from a foundation, industry, or other non-federal sources, but its rules (see note 8 also) can protect the postdoc and minimize the chance of such support. To that end, NIH support for foreign postdocs should begin within <1 year of award of the PhD and continue for at least 4 years thereafter (terminated only by leaving the lab, postdoc malfeasance, or termination of the NIH RPG); if the postdoc is supported for a fifth year, the job opportunities and search must be documented in writing and reported to NIH.

10. TRR (cited in note 2, above), pp 38-9.

11. If a postdoc position in an RPG application is awarded, at any point in the first year of the award the PI could replace it with a position for a staff scientist (one per RPG). In such a case NIH would increase the grant award by an amount equal to the difference between new postdoc-stipend-plus-benefits and the new staff scientist-salary-plus-benefits, subject to certain stipulations, including: (i) the substitution would be allowed only if the grant is to be funded for at least three years after the new staff scientist’s first day in the position; (ii) continued funding of the staff scientist position will not be guaranteed at the time of grant renewal, but instead must be justified in the competitive application for renewal and approved as a result of the review.

12. In early years of the staff scientist initiative, by way of encouraging institutions to impllement one-year bridging funds for staff scientists as permanent policy, the NIH could stipulate that will pay the staff scientist’s bridging salary for the second six months of the bridging year, providing the institution (or the PI, from non-NIH funds) pays the first six months’ salary for that year. It would be reasonable for the NIH to make this commitment only for staff scientists hired in the initiative’s first two years—later hires would be handled by the institution alone.

13. See Postdoc problems.

14. I imagine that the host institution would record relevant data at each of these stages. For instance, for prospective postdocs, data should include academic records, Graduate Record Examination scores, and evaluation by one or more prospective PI. Upon completion of postdoctoral service, the performance of all postdocs who entered the institution’s labs—including those who receive H-1B visas—will be formally evaluated, with a record of accomplishments (e.g., published papers, patents, etc.), a brief note by the PI, etc. After the postdoc leaves the institution, its Office of Postdoctoral Research will also monitor compliance with the payback requirements, and in the process will record information about the postdoc’s location, job and visa status, publications, etc.

I enjoy your blog very much, and find your analyses very insightful. I think nearly all of your proposals are excellent, but I am puzzled by the suggestion that foreign postdocs be required to pay back their training with time spent in a permanent research position in the U.S. Where are these mythical permanent positions that they are to fill? The postdoc holding tank exists because there is a shortage of permanent positions in research for Ph.D. trained scientists. The majority of postdocs that I have worked with, both foreign and domestic, would be very happy to find permanent positions in research at the staff scientist level, but these seem to be in as short supply as PI level positions. If a small percentage of foreign-born postdocs opt not to enter the competition for permanent jobs here in the U.S. but instead prefer to return to their home countries sooner rather than later, won’t preventing them from making this choice only exacerbate our holding tank problem?

Ms. Radisky, you are right to note a potential contradiction. I proposed the payback arrangement mostly because I thought it a good idea (and still do), but also sort of “on spec,” to see if anyone was really listening. I’m delighted to learn that someone was really paying attention – thank you! The idea of payback is justified in part by the fact that (at present, at least) a postdoctoral position in the US furnishes foreign PhDs a first-rate springboard for entry into state-of-the-art biomedical research, and so it is worth their “paying back” for that privilege. It IS hard to get a permanent position, but if one imagines “permanent” to extend beyond “academic tenure-track” it isn’t really all that far a fetch for good to very good postdocs, even now. And one function of the payback would be to discourage foreign students who hope to use a postdoc in the US as a route toward a less competitive position in another country – in other words, for the US to use the payback as a way to get something for what it gives out. Foreigners who are well informed about job opportunities (or the lack thereof) in the US will have to decide whether they want to take the risk of a payback – and, if the market really works, the better ones will apply for visas.

In practical terms, however, a cap on visas for academic postdocs will prove an even harder sell than the payback itself, so that the push for either or both will take several years. During that time I’m hoping that the other steps I proposed (cap on years of postdoc and incentives for hiring staff scientists) will have begun to deplete the postdoc holding tank, so that competing for permanent jobs may have become less scary. Another way to use the payback is to make it conditional on successful application for the first stage of getting a green card. Those who apply for a green card but are told (by the INS?) that they are unlikely to get one would be exempted from the payback requirement. As you can see, I am far from an expert in this murky world, but hope that thoughtful experts can devise ways to maintain influx of the very best foreign PhDs into the US, and exert more selectivity in choosing them. Who are those experts? How would they propose to make this happen?

–BiomedWatch

Pingback: New iBiology videos focus on young scientists | Future of Research